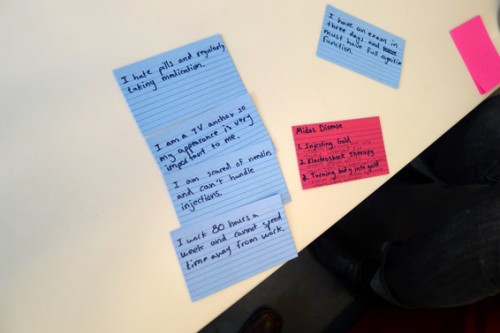

Ideally, medical solutions would be straightforward. If a patient had an illness, they could go in to see a doctor, who would then have a diagnosis and an effective treatment option that aligned with the patient’s preferences and desires. In reality, it isn’t so simple, and there often isn’t a “best” option. Pioneered at Dartmouth, shared decision making involves increased communication between health care providers and their patients, in order to find solutions that best fit patients’ interests. The results seem to be overwhelming, with almost 70% of patients surveyed preferred taking part in making decisions with their doctors (The Guardian, 3/10/12). At tiltfactor, we’ve been working on our shared decision making game prototype. In our most recent game iteration I worked on coming up with potential treatments—such as surgery, topical treatments, or electing to undergo screening, and other actable qualities of a patient—working as a TV presenter, paranoid of needles, or having the responsibility of taking care of two young children.

When I think back to my favorite games in childhood—Set, Pictionary, Scotland Yard, I never thought about their origins. I hadn’t imagined that they went through the initial stages we’re working on now—printing and cutting out tabs, brainstorming on index cards, or Tiltfactor researchers Sukie and Max playtesting a prototype. As a presidential scholar this term, I’ve been able to draw upon a range of different skills to work on the shared decision making project: editing, past experiences with doctors, knowledge of mathematical probability, and an extensive 10+ years of experience playing charades. It’s also wonderful to be working on a topic that I can discuss at dinner with friends as well as with my economics professor. Each day at the lab is different: I may be programming for an Implicit Association Test, proofreading a paper on Metadata Games, or putting together photos for researcher Geoff’s talk at Meaningful Play. We’re all involved in the entire process of creating games for social change—from the original ideas to final products.

Returning to shared decision making, as a Guardian article asked two weeks ago, why is it not part of our everyday healthcare experience? Is there a way that we can help make a collaborative decision making process a norm and a reality? Keep your eyes open for future developments!

Dartmouth-Hitchcock Center for Shared Decision Making