The following is the second in a 3-part series of posts by Tiltfactor student interns. Metadata Games is a NEH-funded open source project that uses games to help crowdsource archive and library holding tags. Below, interns Alannah and Rebecca briefly describe their process for designing a tag verification digital game:

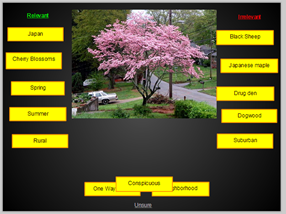

As Tiltfactor enters into what we’re calling the “year of the app” (and other digital formats), a new challenge arises: prototyping digital games. How can we use analog methods to test the interfaces and experience of a digital game? We set out to create a game with a drag and sort interface that would help verify information (i.e., existing metadata) about images through gameplay. We started with paper prototypes: an image and a set of notecards with descriptor tags written on them. The players enjoyed the game and accurately sorted the tags, but we, the developers, were right there. What if we weren’t sitting there? Would they still give us accurate information even with nobody around? Next we tried to mock-up an anonymous digital test using a rudimentary PowerPoint presentation. But this became finicky and lacked the charm of a true drag and drop touch interface. Despite our struggles, we still harvested a lot of information about our design. It wasn’t quite the information we were hoping for, but it was useful nonetheless.

One of the biggest lessons we learned through this process is that you never have it right the first time. We started out thinking we would just test different game mechanics on paper – no skins, no real game feel. While the importance of the game feel became apparent, we were also surprised to find an intrinsic value in the game we didn’t know was there – people took a genuine interest in wanting to help, or try to help, identify the pictures we were presenting. They liked trying to pull relevant data out of the images. This was reassuring.

As we moved deeper into our prototypes, we began to test for more obscure and specific tags. If players were given a bunch of unfamiliar or funny but irrelevant tags, would we still get accurate data? Through our prototypes we learned that some players simply didn’t know what was in the pictures. Once we reached a certain specificity in the data, it was no longer reasonable common knowledge. We realized that in order to crowdsource data, we needed to have an informed crowd. So when we start searching for specialty data, we’re going to have to find a specialized crowd either through some form of filtering or deliberate searching. Despite the limitations of analog prototypes for digital games, we still gained key insights.