Puyo Puyo games are simple puzzle games that require the player to rotate falling pairs of objects to build combos of four or more of the same color. If the objects aren’t matched, they stack up and if they reach the top, the game is over. As the levels progress, players must rotate the pairs more quickly in order to survive, as the speed at which the pairs drop increases.

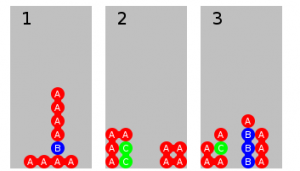

One commercially successful example of a Puyo Puyo game that I played as a child is Sega’s Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine. The final level is depicted below, so you can get an idea of the gameplay.

The final level from Sega’s Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine

Needless to say, earlier levels “train” the player’s reflexes to be able to respond to and rotate the pairs fast enough to succeed in later levels. In the end, the player must respond almost instinctively in order to win.

One of the skills that are essential to success in STEM fields are visual-spatial skills. Sheryl Sorby’s research on building spatial skills suggest that most people believe they initially have poor spatial skills, but that they can be brought up to speed and trained fairly quickly via a training course (Sorby 2009).

I wonder if there is any correlation between people who played and succeeded at games like Puyo Puyo, which require extremely dextrous spatial reflexes at later levels, and their spatial reasoning skills later in life. If so, is it possible that these games could be modded to include a third plane of rotation (i.e. forward/backward) in addition to the traditional 2D rotation required to succeed? How would this impact players’ spatial reasoning? Could they also incorporate examples from spatial reasoning tests in order to familiarize players with these exercises and build their confidence within a game, instead of a course?

I can’t say for certain that these correlations exist, but it’d make for an interesting approach to our NSF project.

References: