MONARCH is a game by Tiltfactor director Mary Flanagan, illustrated by Kate Adams. The game is currently seeking funding on Kickstarter. Max Seidman worked on the design of MONARCH’s mechanics and Mary calls him “the balance expert.” Max also runs a game design theory blog, Most Dangerous Game Design. Here, Max shares thoughts on our intentional design that balances complexity with an unfolding, or “elastic,” design to suit a range of players’ interests and playstyles.

At Tiltfactor, I’ve had many occasions to informally study how players with little to no strategy board game experience have their first interactions with strategy board games. I’ve run MONARCH and other games for over a hundred (if not hundreds) of 6th-9th graders, the extent of whose board game experience is Sorry! While the primary purpose of almost all of these sessions were to gather formal data for the research studies that we conduct at Tiltfactor, they also served as excellent playtests with a very commonly overlooked audience: “non-gamers.”

To be clear, no designer wants their game to be unapproachable to new gamers. Unfortunately (especially in the rural woods of New Hampshire) there tends to be a big selection bias for game playtests; the players who volunteer to try your games are the people who are themselves really into games.

These broader playtests allowed me to make one core observation about how these players interact with strategy games, which in turn have made MONARCH the game that it is today: for non-gamers, choices in strategy games are scary. Time and time again I would watch 8th grade players continually harvesting and taxing, and then hoarding their resources without spending them. It’s not that these playtesters didn’t understand how to play the game—they completely understood that without spending their resources they couldn’t win. Nor are these players stupid; they were simply timid about committing themselves and their resources before fully understanding the game. This poses a major problem when trying to design tabletop games for both strategy game experts and novices, since interesting and challenging choices are exactly what experts want to see in their games. How do you design a board game so that its choices don’t scare away novice players, while still providing challenging decisions for expert players?

Scaffolding and Default Actions

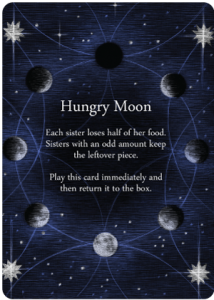

I’ve written in the past about some fairly straightforward ways to make strategy tabletop games more accessible to everyone. Scaffolding, for example, is the process of slowly introducing elements or escalating the difficulty of choices in a game, so that new players aren’t overwhelmed at the start. MONARCH, of course, has some of this. For example, the game’s 8 Moon cards are events that often cause the players to debate and negotiate about who’s going to contribute to help the realm. Because players don’t usually run into Moon cards for several turn in the game, the Moons are one element that players don’t need to understand or worry about until they run into the first one, thus allowing players to focus on learning all of the elements they do need to play the first few rounds of the game.

Pro players, of course, learn not to hoard their resources and look out for this one.

In addition to scaffolding, many of the more popular and approachable tabletop games of the last century have a particular mechanism in common that I’ve been calling a “default action.” A default action is simply one that a player must take at the start of his or her turn which provides some benefit to him or her. Monopoly’s default action is rolling the dice and (sometimes) passing go and collecting $200. Catan’s default action is rolling the dice and collecting resources. Bohnanza’s default action is planting the first bean card in your hand. MONARCH follows suit with its harvest/tax mechanic, simply allowing the player to bring in more resources of the type of his or her choice.

Elastic Design

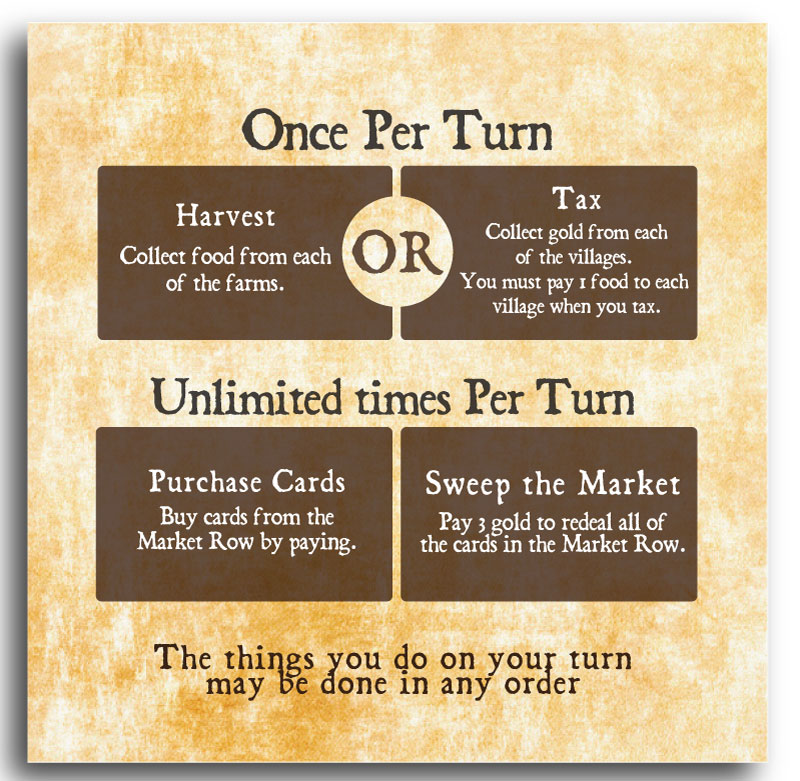

On your turn in MONARCH, you can do several things in any order:

- Bring in new resources by Harvesting or Taxing, once per turn.

- Purchase cards from the Market Row, including Court Cards, Unwanted Guests, and Land Improvements, as many times as you want/can afford.

- Sweep the Market Row to put out a set of new cards, as many times as you want/can afford.

Early in the development of MONARCH, we observed that novice strategy gamers had a major issue with this structure: they were extremely hung up on the concept of doing these actions in any order—and for very good reason. Turns provide much more interesting decisions when a player can first purchase a Land Improvement, then tax, using that Land Improvement to get extra gold, then sweep the Market Row to look for new Court Cards to purchase, and then purchase more Court Cards. While these choices are interesting for expert strategy gamers, they’re overwhelming for novices.

To remedy this problem we employed a method that we’re now calling ‘Elastic Design.’ Elastic Design is a particular form of scaffolding that allows players to ignore complexities until they’re ready to deal with those mechanics. For the order of actions problem described above, we began to teach the game by saying, “On your turn you tax or harvest, then you purchase Court Cards,” while at the same time giving each playtester a reminder card that clearly stated that the actions can be done in any order. This structure proved very helpful for novice players; for the first half of the game they would first tax or harvest, and second purchase court cards. Inevitably, one of the players would eventually notice the “in any order” phrase on his or her reminder card, and proceeded to Improve a land, and then tax or harvest, thus introducing the interesting turn ordering choices to the rest of the group, but only after they had become familiar with the rest of the game.

Elastic design is ‘Elastic’ because it allows game mechanics to “stretch” to fit the preferences of the players playing the game. Image by Bill Ebbesen under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

We found that novice players had a similar reaction to Sweeping the Market Row, which is a crucial component of the game and one of the few ways in which players can interact with their opponents. So our team implemented a similar solution: we didn’t mention sweeping while teaching the game, and simply left it up to the players to see it on their reminder cards and introduce the concept themselves. These experiences informed the way the MONARCH instructions were written: placing the most emphasis on the most crucial parts of the game (for example, Harvesting/Taxing), and allowing the more complicated processes to be opted into.

Sweeping is replacing all of the cards in the Market Row with 5 new cards. Much like the similar mechanic in King of Tokyo, it’s not free to sweep.

Where many games simply break if the players don’t understand or overlook a particular mechanic, elastically designed mechanics are allowed (and designed) to be overlooked until the players are ready to handle them. Elastic design differs from most game scaffolding in that an elastically designed mechanic’s introduction into gameplay is purely organic, relying on the players to have an epiphany and being to leverage it, whereas traditional scaffolding somehow schedules or scripts the reveal of new mechanics. Many games have mechanics that are ignored by players as a house rule (Monopoly’s little-used auction mechanic, for one). Elastic design can obviate the need for these house rules: if designers can anticipate (through playtesting) how their games will be interacted with by different audiences, they can work to elastically design elements that would otherwise cause novice players pause, which will increase their games’ approachability.